Hot Talk

What's Stopping the Talk About Climate Change and How You Can Become Empowered to Speak Your Mind About Global Warming

By Sarah Mosko

How often do we talk about climate change to family, friends or coworkers? Probably next to never if we’re like most people.

Credit: Sander van der Wel

Yale’s national polling reveals that the majority of Americans accept that global warming is happening (73 percent) and are worried about it (63 percent). Even more want carbon dioxide, or CO2, regulated as a pollutant (81 percent).

Given these stats and the warning of scientists that the time window to prevent the worst impacts of climate change is closing fast, what keeps us from openly discussing it?

The answer is complex. For starters, many of us were raised in a bygone era where talking politics (and religion) was considered simply impolite. That climate change has become such a politically divisive issue adds weight to the interpersonal risk people naturally experience in bringing up any sensitive topic, even with intimates.

There is also the fact that humanity is ill equipped to respond to the kind of threat posed by a warming planet. Addressing climate change demands an approach to problem solving outside our past experience as a species. Humans are quite adept at addressing “here and now” challenges like putting out a forest fire. However, human history has not prepared us to respond to, or even easily comprehend, a long-term global problem like climate change because it unfolds so gradually over time and in the form of exacerbation of happenings not completely new to us.

For example, while we can accept that the average global temperature is rising, climate change is thus far being experienced in our individual lives primarily as an increase in weather extremes, like record-breaking temperatures and more violent storms. Because such events are not completely unfamiliar and we never know the extent to which climate change contributed to any one, we can’t feel the immediate urgency of the problem like we would if it stuck suddenly like an earthquake or explosion.

Moreover, the human psyche is resistant to tolerating for long the kind of unease one feels when thinking head-on about the terrifying consequences of unchecked global warming, such as accelerated species extinctions, spread of diseases, mass human migrations, and increases in social unrest and wars. The urge to veg out instead in front of the TV is understandably very human.

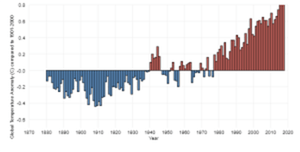

Annual average global temperatures since 1880 (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

But human nature deserves only some of the blame – our politicians and the media are also culpable. Both have participated in the devaluation of science that makes possible that many in the public are unaware or suspicious of some basic facts, e.g. that more than nine out of ten climate scientists and nearly three out of four Americans are convinced that global warming is real.

The complicity of politicians and the media in ignoring climate change was blatant during the 2016 election season. As tallied by Fairness & Accuracy in Reporting, exactly zero questions were asked on the topic during the presidential and vice-presidential general election debates, and the few mentions of climate change by Hillary Clinton were made in passing.

Both our elected representatives and the media are entrusted with keeping the public informed about the important issues impacting our individual lives and the nation as a whole. This should include straight talk about climate change solutions at every opportunity. Instead, they default to inflammatory “red meat” issues like abortion and gun control, conveniently keeping the public’s attention diverted from noticing that those societal institutions are abdicating their fundamental obligation to the public in service of appeasing corporate sponsors.

Atmospheric CO2 levels over past 800.000 years (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

For all of these reasons and more, the public is left feeling personally impotent to do anything about climate change and fooled into thinking that our societal institutions are powerless too. The main point I want to make here is that our elected representatives in Congress are fully vested with the legislative power to address the problem effectively and globally, if only they would.

There is strong agreement among economists (both conservatives and liberals) that the only realistic answer to climate change is to implement a market-based solution that puts a gradually rising fee on carbon emissions worldwide to effect the necessary transition from a fossil fuel-based global economy to one reliant instead on renewable energy sources. Congress needs only to find the political will to pass a revenue-neutral price on carbon as it enters the economy (at the well, mine or port) along with a border tariff on imports imposed on countries that fail to follow to suit.

Revenue-neutrality means that the money collected is passed to American households on an equal basis in the form of a monthly dividend. Studies show such action would strengthen our economy, while effectively addressing the problem.

The size of the U.S. economy empowers us to lead the world to a green energy future, but nothing will happen without Congress stepping up.

The upcoming mid-term elections are an opportunity to make the contenders accountable for their stance on climate change and to rout out any that are impediments to enacting a solution. At minimum, we can visit each candidate’s website to see if climate change is even listed as one of their “Issues.” Or, type “climate change” into the website’s search feature to see what it produces.

To gain comfort in talking about climate change in our day-to-day lives, the five tips offered up by philanthropist Jane Burston might come in handy. For example, she recommends focusing on how climate change is already being felt – like 17 of the hottest 18 years in recorded history happened within the last century – rather than on dreadful ways it could play out in the future.

Also consider reminding others that heads of major gas and oil companies support the Paris Climate Agreement.